The Greatest Athlete

By Bob Welch (Register Guard - Eugene, OR)

August 29, 2004

AS THE GREATEST athletes in the world bid farewell to the Athens Olympics today, I find myself thinking about the greatest athlete I've ever known.

I met him on the sidelines of a church turkey bowl football game on Thanksgiving 2002. I wasn't playing because I'd torn ligaments in my knee. He wasn't playing because he didn't have a right leg.

Bryant King, then 11, looked longingly out at the field, wearing a Green Bay Packers jersey that hung on him like a parachute.

"Wanna play catch?" I said.

He said sure. I stepped toward him and tossed the ball underhanded as you might to a 3-year-old. He caught it with ease - ever try catching a pass hopping on one leg while letting go of your two metal canes? — and gave me a "have-a-clue" look.

"Go out for a pass," he instructed. In slow motion, I started "run-ning" away from him. "Faster!" he yelled. I picked up speed. Bryant cocked his arm and zipped a spiral to me as if he were a pint-sized Brett Favre.

Mia Hamm kicks a great soccer ball, Michael Phelps swims like a fish, Roman Sebrle sets decathlon records. But when it comes to the world's greatest athlete, I'm sticking with Bryant King, the only human being I've seen kick dead-straight field goals while balancing on a cane, the football teed up in a cut-off toilet-paper tube.

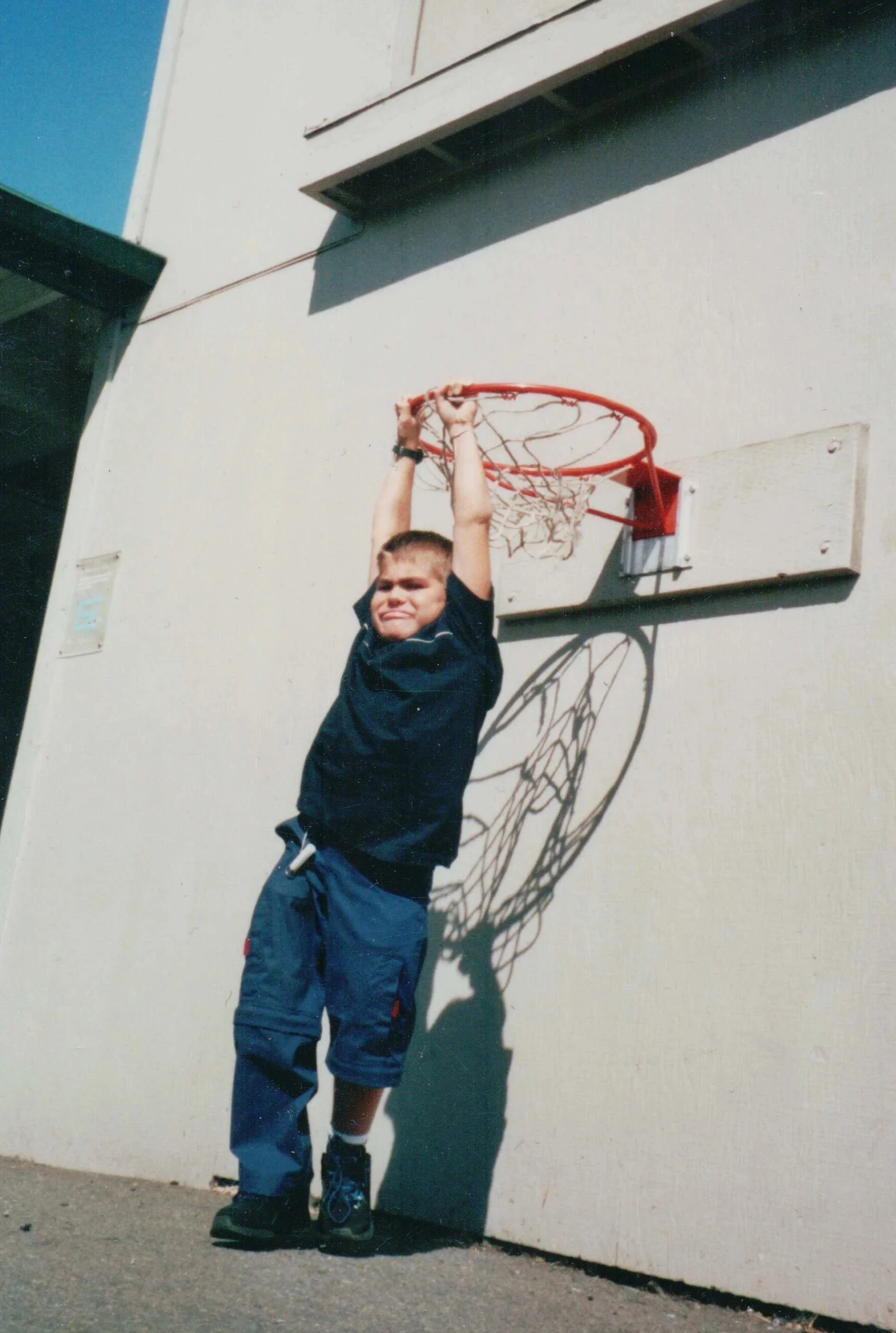

If there's a way, Bryant will find it. Soccer. Baseball. Basketball.

Badminton. Air hockey. Ping-pong. He's played them all. His room is sprinkled with Kidsports trophies. "It's pretty amazing to see him get up and down the basketball court," says Andy Hill, a friend and fellow Monroe Middle School eighth-grader. "He scores points. And if he can't do something, he motivates others."

He skateboards, drives ATVs and rides a bike. Last year, he wanted to try knee boarding behind the Kings' boat. His parents, Steve and Lisa, were skeptical. But soon Bryant was doing so well that his grandfather, Emile Mortier, bought him a board of his own.

In rare moments of inaction, he dreams and schemes in one of 12 spiral notebooks. "What I need for a go kart" is one heading. Other topics include "What I would wear snowboarding," "How to make money" — including "Be on 'Fear Factor' " - and "What to be when older" (pro paintballer, video game inventor, singer, host of a sports quiz show and 17 others).

Bryant, 13, has brown eyes and shaggy brown hair. Once, I told him he looked a lot like - "I know, Luke Jackson. Everybody says that." Only Luke Jackson is 6-foot-7 and 215 pounds. Bryant King is 4-foot-1 1/2 and 68 pounds.

Luke is Bryant's hero. His room and wardrobe pay homage to the ex-University of Oregon basketball star. But would Jackson still be great if he'd had more than 20 surgeries? Were on his second kidney transplant? Had been tube-fed for the first 11 years of his life?

Such has been life for Bryant King, who was born with caudal regression syndrome, a disorder affecting the legs and lower intes-tines. "He just won't be stopped," Steve King says.

He's suffered four broken legs. Spent a year traveling to Corvallis and Portland for kidney dialysis. And recently had a spinal fusion, two rods being placed in his back.

"I just do what I can," he says. Once, kids at school were reluctant to let him play hoops.

"I don't get bitter," he says. "T just try to prove it. Then they're like, 'Whoa.'"

Another "whoa" came in the spring of 2003 when he was playing in a wheelchair basketball game at Mac Court against UO players. At one point, Bryant found himself guarding a guy whose picture hangs on his bedroom wall: Luke Jackson.

Bryant rolled up and began applying defensive pressure. Jackson got flustered. He lost control. His wheelchair tipped over, spilling him out.

"It was pretty funny," says Bryant, who wound up with the ball.

"Basically, I schooled him."

New category for my spiral notebook: "What to add to my office: autographed picture of Bryant King, my hero."